The three words that seemingly shoot fear and apprehension through many of us, whether we exercise frequently or not. If you’ve ever had a problem with your shoulder, there’s a pretty decent chance that the rotator cuff was involved in one way or another. However, is the reputation it holds a fair one? Let’s look into what it is, what it does, what tends to go wrong, and what we can do about it.

Housekeeping

If you haven’t yet had a chance to read about the complex anatomy of the forearm, tap or click the link below.

As always, you can access my other materials, including my FREE guide: 20 Habits to Change Your Life. If you want to access this, tap or click here.

A reminder:

You can get 10% off your Awesome supplements by using the code ‘EZEP’ at checkout. More information can be found at the bottom of the page.

The 4 muscles of the rotator cuff

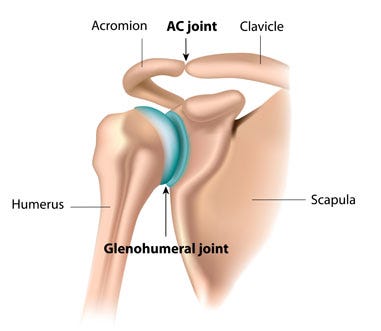

Last week we looked at the twenty muscles in the forearm. This week is much more straightforward! The rotator cuff refers to just four muscles which help support and stabilise the shoulder joint, specifically, the glenohumeral joint, which is where the humerus (bone of the upper arm) meets a part of the shoulder blade known as the glenoid. In the simplest terms, you can think of the glenohumeral joint as the traditional ‘ball and socket’ of the shoulder.

To remember the four muscles of the rotator cuff, we can use the acronym S.I.T.S. Details of the muscles, in acronym order, can be found below.

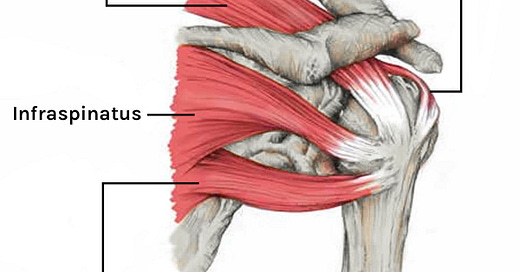

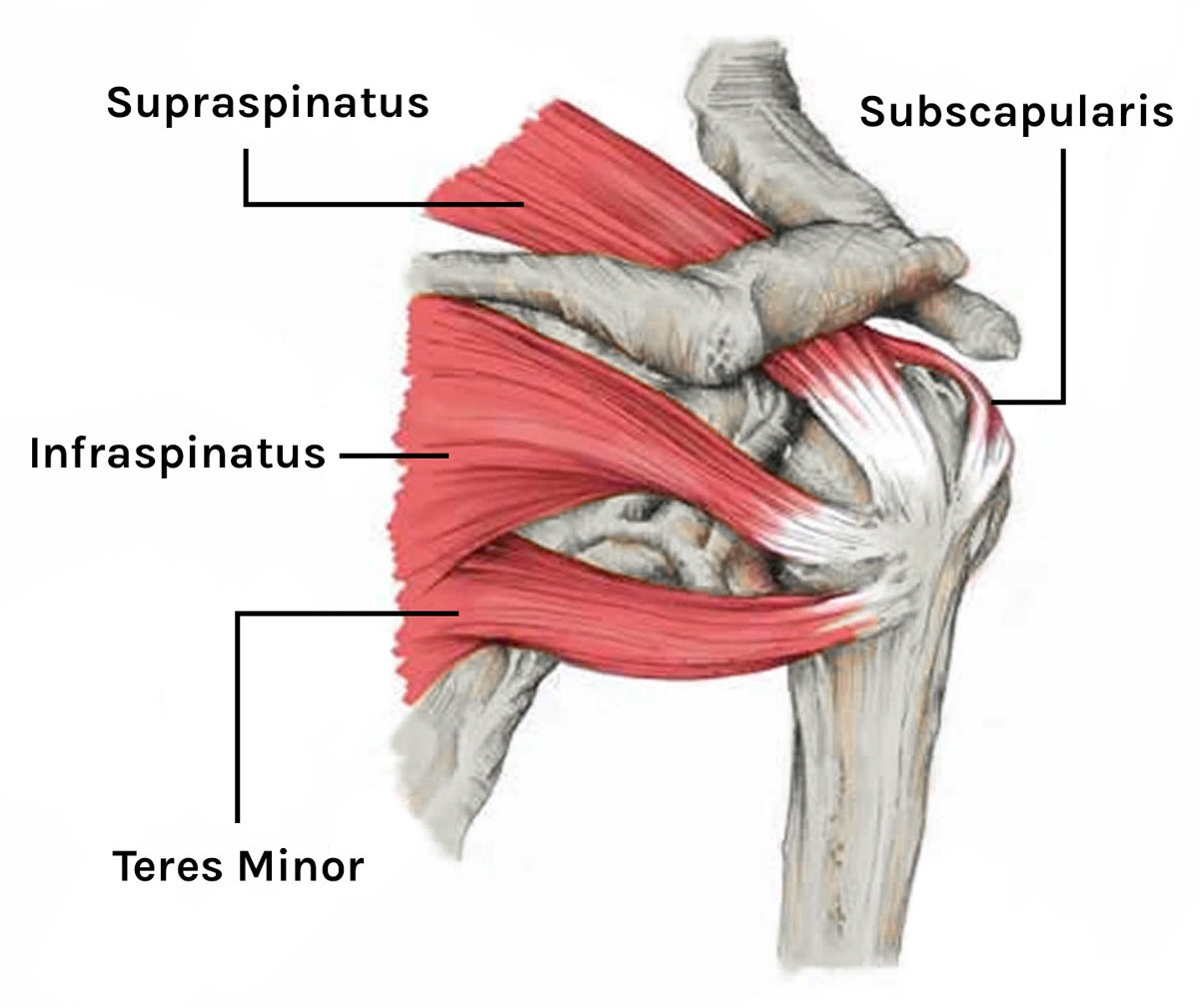

Supraspinatus

The supraspinatus is the ‘highest’ or most ‘superior’ of the rotator cuff muscles. This makes sense, since ‘Supra’ means above. However, it is also the smallest, and most often injured of the muscles.

Infraspinatus

The infraspinatus is the next muscle down and gets its name from this fact - it is literally ‘down from’, or ‘inferior to’ the supraspinatus, specifically the spine, or thorn, of the scapula bone.

Teres minor

The teres minor is the most strangely named of the four muscles. The ‘teres’ aspect of the name refers to the fact that the muscle is slightly ‘rounded’ (although no more than the others in the rotator cuff if you ask me)!

Subscapularis

Finally, the subscapularis is the only of the four rotator cuff muscles which is located anteriorly to the scapula. The name literally means ‘under the scapula’. The subscapularis is also the largest and strongest of the four rotator cuff muscles.

Functions of the rotator cuff muscles

Now that we know what and where the four muscles are, we must learn about which actions they are responsible for, as this will help us to understand how they contribute to certain movements during exercise and any potential causes of injury. We shall take a look at each muscle in turn below.

Supraspinatus

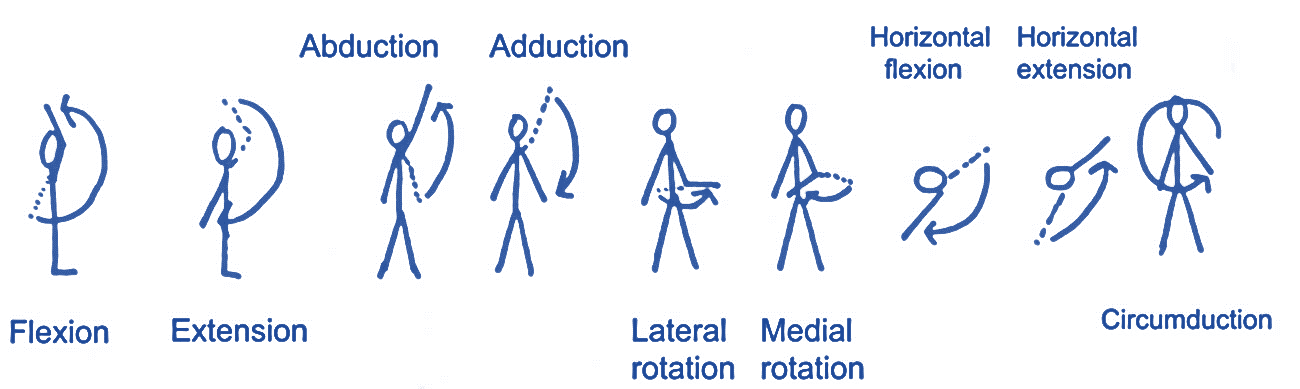

The muscle runs from the top of the shoulder blade and joins onto the head of the humerus, and is primarily responsible for the first 15 degrees of shoulder abduction (I have included a picture of some common shoulder movements below). After the initial 15 degrees of abduction, another muscle called the deltoid takes over the majority of the work, and the supraspinatus gives it a helping hand up to 90 degrees. As a result, the supraspinatus helps stabilise the joint in overhead movements, which is one reason why it can be susceptible to injury.

Infraspinatus and Teres minor

The infraspinatus and teres minor muscles are primarily responsible for a movement known as external or lateral rotation, in the centre of the image below. As the name suggests, external rotation is useful for turning the arm outwards, away from the torso, and as a result, is vital for many movements in life and sport, such as throwing and catching, or swinging a racquet or club.

In addition to external rotation, the infraspinatus and teres minor also play a small role in shoulder extension. The teres minor also aids with shoulder adduction.

Subscapularis

The subscapularis is the main antagonist to the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles; it provides internal rotation. Logically, this is the opposite movement of external rotation.

It can also help with shoulder extension and adduction depending on the position of the arm.

Injuries

Typically, at this point of the newsletter, I’d outline some unique injuries specific to the muscles which had previously been outlined. Since we are looking at a very specific group of muscles today, it is very rare to experience injuries other than traditional tears, tendinopathies, and tendinitis of the rotator cuff muscles.

As mentioned earlier, the number one cause of injury with the rotator cuff, especially in younger populations, appears to be any action which has a heavy overhead emphasis. This could be lifting weights in the gym, or throwing, catching, pitching, or swinging, and tends to irritate the supraspinatus more than the other muscles.

Strangely, pain may not always be present in the aftermath of a rotator cuff injury. Sometimes, there may just be a weakness during certain movements, such as external or internal rotation, abduction, and extension. Most often, pain is associated with these movements, depending on the specific muscle which has been injured.

In the case of the subscapularis muscle, there are certain trigger points or places where pain is more severe. Some of the limited range of movement caused by these trigger points can overlap with the pain induced by a condition known as ‘Frozen Shoulder’ or adhesive capsulitis. It is therefore always recommended to see a specialist if you have any ongoing pain or suspected injury to the shoulder, so to get a correct diagnosis, as a frozen shoulder can remain a problem for many months.

In the case of tears and tendinopathies, the treatment tends to be pretty standard: Rest, anti-inflammatories and ice initially, followed by heat after 72 hours. Then, it is a case of optimal loading and rehabilitation exercises. I shall outline some specific exercises in the following section.

Strengthening the rotator cuff muscles

As always, selection of exercises to strengthen the rotator cuff is easy now that we know which actions the muscles are responsible for. We know that the rotator cuff muscles are responsible for: abduction (or at least the initial phase), external rotation, internal rotation, and adduction. The following exercises can therefore strengthen the entire cuff.

Band or cable external rotations

Band or cable internal rotations

Lateral raises (will switch over to the deltoid muscle after the initial phase)

Prone ‘Y’ raise

These exercises can, handily, be scaled down and made easier in case of rehabilitation, or scaled up if a greater challenge is needed. Whilst this list of exercises is not exhaustive, it will do a great job of strengthening those four rotator cuff muscles if done regularly, correctly, and with a sensible load.

A shorter than usual ‘Muscle Monday’, but I hope you found it as insightful as always. We have a couple more major muscles to look at before we switch over to a ‘Workout Wednesday’ focus. If you have any specific muscles you’d like to look at, please let me know in the comments below. See you next time!

“Teres” muscles are so named because when transected and viewed in cross section they are round.

Is it safe to do the suggested exercises if all four tendons have been partially torn? I don’t want to have a complete tear. Thank you.