If you have ever been given a ‘stress score’, ‘recovery score’ or ‘readiness score’ by a wearable device, you’ll probably have already encountered Heart Rate Variability (HRV), but what is it, and why is it important?

Today’s blog is written in association with Fitlife Summertown. If you live in the Oxford area and looking for PT, or maybe you don’t live nearby but are looking for remote specialist exercise support, get in touch by tapping ‘Message Ben Howard’ at the bottom of the page! Alternatively, feel free to check out my website or Instagram. See you there!

Interest in HRV has skyrocketed recently. Wearable devices, such as Oura, Whoop, Garmin and Apple Watch now allow anyone to observe their scores either directly or through a mobile app. But what is it?

We are not machines…

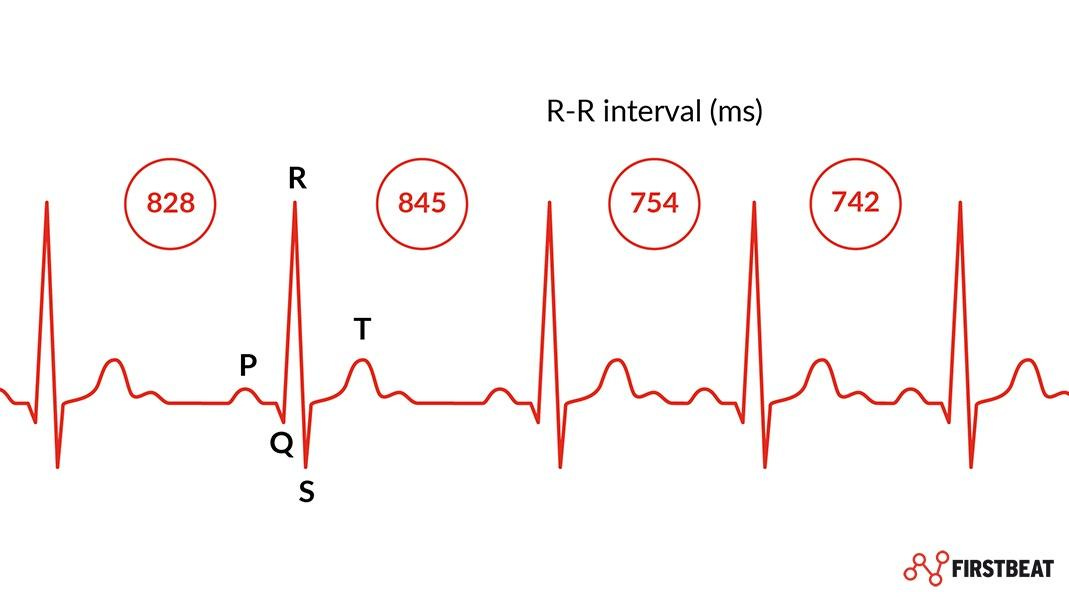

Put simply, HRV refers to the variability in time taken between heart beats. Imagine that you have a resting heart rate of 60bpm. You may think that this equates to one beat every second (or one beat every 1000 milliseconds), but in reality, there are likely to be small variations in the time taken. This is a good thing - a healthy heart is not metronomic in nature, and there should be some base-level of HRV in the vast majority of healthy individuals. HRV is not something you can necessarily feel, and generally requires some equipment or software to assess your heart rhythm and generate an output like the one seen in the image below. In this example, the time taken from one R wave to the next* varies from 742 to 845ms.

In theory, the slower the heart rate, the greater chance there is of an increased HRV. This does make sense - if there are fewer beats occurring per minute, then there is a higher likelihood of greater variation in time between these beats. Conversely, the faster the heart rate, the greater the likelihood of a lower HRV, as there is less possible time between beats.

So, hopefully you now can understand that in general, a higher HRV is considered ‘healthier’ and a lower HRV may be less optimal.

*R waves are the peaks in heart rate traces as seen on ECGs, and the gold standard measure for HRV. Most wearable devices use special lights (generally green in colour) to detect heart rate, and then infer the time taken between beats, known as the Inter-Beat Interval, as a substitute for strict HRV.

An Insight Into The Autonomic Nervous System

Ultimately, HRV analysis is the best, most widely-accessible, cost-effective way to gain insight into our own autonomic nervous system.

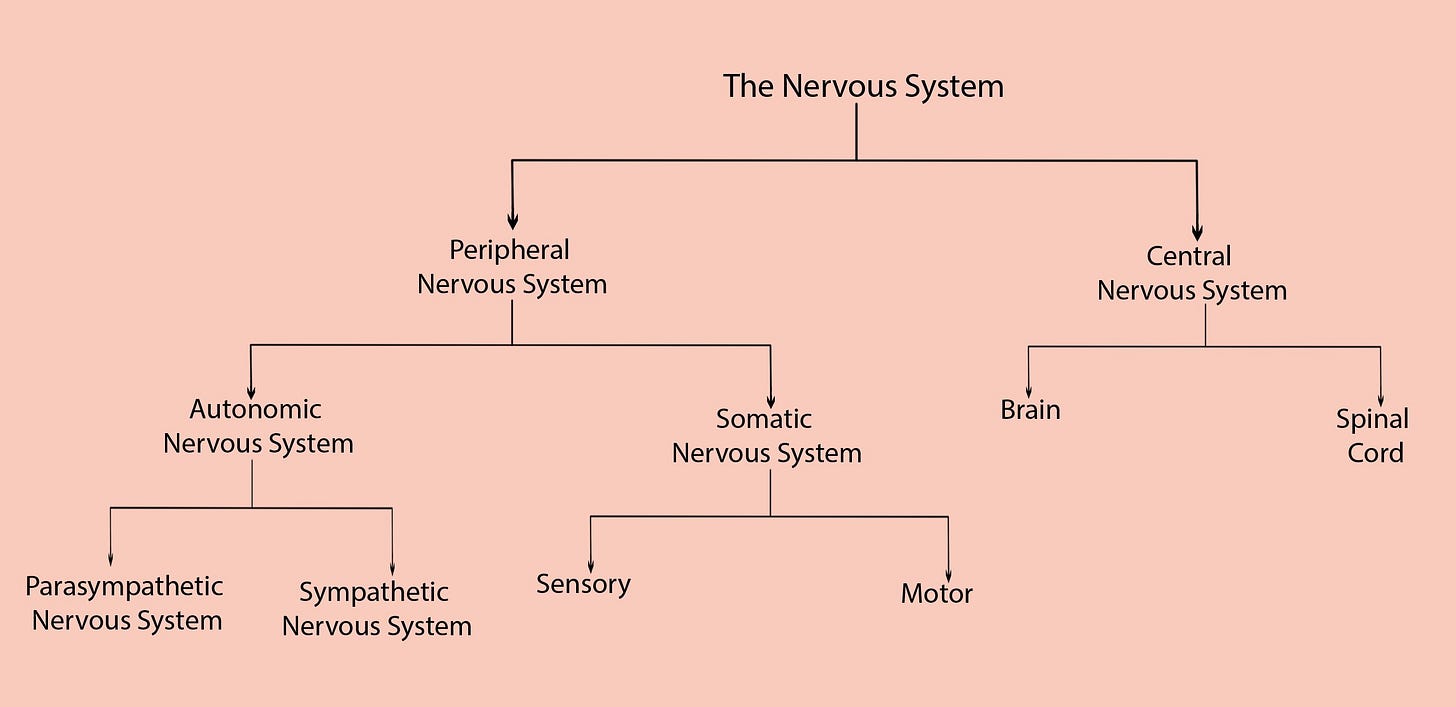

As you can see in the image below, our nervous system is divided into many smaller segments. The brain and spinal cord make up our central nervous system, with everything else being assigned into our peripheral nervous system.

The peripheral nervous system is then further split into two categories: The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for all involuntary functions, including breathing and heart rate, whilst the somatic nervous system controls voluntary functions, such as the muscle skeletal muscle contractions required to walk and run.

If we zoom in on the ANS, we can see two further sub-divisions.

The Parasympathetic nervous system is the ‘rest and digest’ dominant system, likely to take charge when feeding, resting, or recovering from stress. This system decreases heart rate and subsequently increases HRV.

The Sympathetic nervous system is the ‘fight or flight’ dominant system, which is activated at times of heightened stress, fear, anxiety, or physical activity. This system increases heart rate and subsequently decreases HRV.

As a general rule, based on the information above, we know that we should have a greater HRV during periods of rest and recovery, and a lesser HRV during periods of physical or mental stress. However, life is never this simple.

It is now common to see individuals with a chronically low HRV, either despite, or due to a lack of, periods of rest and recovery. I myself see many individuals who do not improve in HRV overnight, indicating that they may be chronically over-stressed, and ‘stuck’ in a state of sympathetic nervous system dominance. Some professionals define this as ‘poor stress resilience’, since the body is struggling to cope and recover from periods of stress. This stress may take the form of mental stress, or physical stress - and in active individuals, this could indicate a state of overtraining. Either way, this is bad news for your heart health; chronically low HRV is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease and even poor mental health.

How to improve HRV?

If you are worried that your HRV may be chronically low, there are many steps that we can take to help. Whilst there is a genetic element to HRV, helpful tips include:

Accumulating at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise, or 75 minutes of intense exercise, per week.

Resistance training on at least two days each week (Check out my recent blog with a template on how to achieve this.)

Improving sleep habits (see my sleep posts 1 and 2 for help with this).

Reducing alcohol intake

Take time to work on your downregulation. This can take the form of mindfulness, breathing techniques, yoga, meditation, and journaling.

Want to know more?

If you are interested in assessing your HRV to a medical standard, and not simply through a wrist-based wearable, get in touch - I now offer a stress resilience service that may interest you…hit the button below for more information!

See The Real Science of Sport podcast about how inaccurate these devices are.

I personally have found HRV incredibly useful in highlighting things I should avoid. When I discovered how much alcohol negatively impacted HRV it made it much easier for me to cut back. I’ve seen other important trends like exercise, sleep, and medications and how they impact HRV to be more aware of my health. I often recommend my patients track HRV to get a better sense of stress on the body when undergoing cancer treatments. I plan to explore this as a deep dive soon.