Here’s the problem. In the UK, only ~16% of the population regularly goes to the gym. So, well over 80% of you either haven’t performed any weight or resistance training, or have stopped doing so. The question is this: How does one go about starting, or restarting, resistance training? If you wish to know, then this is the newsletter for you.

Housekeeping

Here are a few quick reminders before we begin:

You can access my entire archive of Muscle Monday and Workout Wednesday here.

You can download my FREE guide, 20 Habits to Change Your Life, here, and explore my other socials here.

You can get 10% off EVERY order, present and future, at Awesome Supplements by using the code ‘EZEP’ at checkout. The creatine monohydrate pack is a great idea for everyone, especially those seeking enhanced gym performance.

Paid subscribers get full access to exclusive newsletters. Upgrade below to gain access to these.

Step One - Pick a goal (or three)

Research clearly shows that setting goals is a great method for increasing exercise compliance. This doesn’t need to be an event, such as qualifying for the Olympics, but it can be to improve by a set amount, hit a weight goal for a certain exercise, or simply to keep consistent for a set number of weeks.

There are two methods for goal setting which I find useful.

Stay S.M.A.R.T

The first of these is the well known S.M.A.R.T goal framework. This states that any goal should be: Specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and relevant, and time-bound. Examples of goals which comply with this structure could be:

“I would like to improve my bench press 10 rep-max by 15% from my baseline measurement within 6 months.”

“I want to have attended the gym at least twice per week, every week, from now up until the end of the year.”

In both of the examples above, there is clarity around what success looks like. There is also a deadline or end date to provide closure, and a measurable marker of progression or success. This framework is brilliant for giving a very specific, binary goal - you either succeed or you fail. If you feel as though this may provide too much pressure, then my next method is better suited for you.

Bronze, Silver and Gold Goals

For those who would prefer a less pressured, but equally effective approach, my three-tier goal system may be a happy alternative. I call it Bronze, Silver and Gold. Just like with the S.M.A.R.T framework, you need to be specific, realistic and time-bound with goal setting. However, my approach allows you to select three tiers of success. Let’s explain using examples below, based on one of the S.M.A.R.T goals as previously discussed:

Bronze - “I would like to improve my bench press 10 rep-max by 8% from my baseline measurement within 6 months.”

Silver - “I would like to improve my bench press 10 rep-max by 12% from my baseline measurement within 6 months.”

Gold - “I would like to improve my bench press 10 rep-max by 15% from my baseline measurement within 6 months.”

As you can see, the goal has been modified to give three tiers of success. In the case above, I have reduced the level of improvement required for a bronze goal and increased it towards the gold tier. However, the same effect could be induced by manipulating the time frame. You could even do both - give yourself longer to achieve an 8% increase for bronze, and less time for a 15% increase in gold. With this framework, you take the pressure off yourself. You can treat the gold tier as the target if everything goes 100% to plan, and the bronze tier is there to give you a mental boost if things start to go a bit funky. This helps with motivation - at any point in your training, you’ll always have at least the bronze goal to aim for.

Whichever method you choose to select your goal, make sure that you’re working towards a challenge, but an achievable challenge. Nothing is more depressing than realising that you’re miles off the pace after 3 months of hard training.

Step Two - Identify your barrier(s)

Once you’ve set yourself some goals, the next best step is to try to second-guess or predict what may stop you from achieving these goals. There are actually plenty of online tools available for this, including one which I shall attach or provide a link to below. The most common barriers tend to be time and money, but more recently, there’s a decent chunk of evidence citing lack of confidence, skill and social barriers with a drop in exercise coherence. For some of you reading this, a potential barrier may be the fact that you’re coming back from injury, and you’re going to have to psychologically battle with the balance of training risk and training reward. We all have barriers; knowing them in advance of a training plan makes life much easier.

If you think that time may be an issue, then try to schedule workouts into your diary. If money might be a problem, then it doesn’t cost money to go outdoors for a fast walk or run. You can always perform bodyweight exercises, or callisthenics, at home if needed, too. If you need a training buddy to help you through, then ask a friend or family member; chances are they’re just as worried about making a positive health change as you are and would appreciate the support.

Regardless of which specific barriers may get in your way, knowing them is half of the battle. It is much easier to plan around these barriers than to get six weeks into a training plan, then realise you can no longer afford your gym membership or make the time to exercise.

Here’s the link to download the PDF I have created. It’s simple and nothing special, but hopefully you get the idea.

Step Three - Choose a weekly schedule

So far, you’ve set some goals and assessed your likely barriers. With this in mind, you can now start to put together a weekly plan. The first big decision is: How many times per week will you exercise?

This is where I’m going to be controversial. If you want to set yourself a plan of just coming to the gym once a week to begin with, then that’s absolutely fine! You’ll struggle to see progress after a while, but if this sets a solid base and habit in motion, then you’ve already succeeded. I’ve seen so many people say that they want to come to the gym 5-6 times per week, only to burn bright and fast, before stopping entirely after a month. If you’re in doubt here, start once per week and then build up if you’re feeling good. Think of this as the gym equivalent of the tortoise and the hare.

Ideally, you’re looking for two key targets with a weekly schedule:

An adequate training load to allow you to hit your goals

Adequate rest between sessions, since this is when the adaptations occur.

With this in mind, the two most common routines tend to be:

Monday, Wednesday and/or Friday in the gym; or

Tuesday, Thursday and/or Saturday in the gym

These patterns give at least a day between sessions, and can be scaled for 2 or 3 visits per week with adequate rest. However, you can be flexible with this, and come on Monday and Friday, for example. As always, the key here is being able to fit this in around your own schedule, and with your own specific barriers in mind. If you know that time is tighter on a Friday compared to a Sunday, then don’t try to squeeze in the gym on a Friday.

I wouldn’t try to come more than 4x per week when starting or restarting a gym plan. Those initial weeks will be the most likely to feel sore and stiff after a gym day, and there’s nothing more demoralising than exercising on already sore legs or arms. Start gently, then build up.

Step Four - Establish a baseline

In order to be able to measure progress and the efficacy of a training plan, you must first determine your current level of fitness. Personally, I find that assessing 10 repetition maximum (10RM) is a good universal measure. Simply put, this refers to the maximum weight at which you can perform 10 reps for an exercise.

There are two ways to do this. The preferred method is to start at a weight at which you know you can comfortably perform 10 reps, then sensibly increase the load until you find it hard to impossible to perform 10-11 reps for a set. Ideally, you can find your 10RM at the 3rd or 4th set, before muscular fatigue really starts to kick in.

The alternative method here is to use conversion tables or equations. Instead of aiming specifically for 10RM, i.e., hitting failure at exactly the 10th rep, you simply select a weight and go for as many reps as you can. Ideally, you can’t complete more than 12 reps for this attempt. If you can perform more than 12 reps, then try a heavier weight. It may be that, for example, you are able to bench press 104 pounds for 8 reps, and that’s your best effort.

If you want to be precise, there are various equations available online. You simply enter the exercise load/weight, and the number of repetitions you managed to achieve, and the equation will give a pretty good estimate for your 10RM, and even potentially your 1RM, which is the hypothetical heaviest weight you’d be able to perform for just one rep of an exercise.

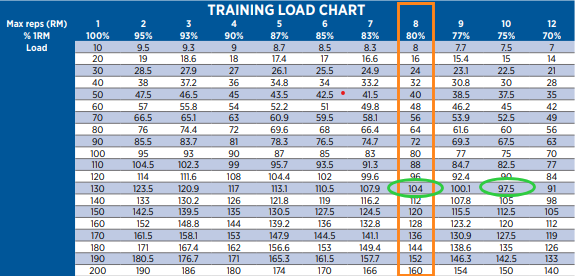

If you prefer, you can use conversion tables, such as this one provided by the NSCA. I’ve included a screenshot snippet of it below. For these tables, you find the column which refers to the maximum number of repetitions you performed, then scroll down until you find the closest weight to the one you achieved. In our example, for the bench press of 8 reps at 104 pounds, we look for column eight and look down until we land on 104.

To calculate 10RM from this value, we keep the same row and move along two to the right (column 8 to column 10 - essentially converting our 8RM to a 10RM), and we see that this estimates an 8RM of 104 to be a 10RM of 97.5. If you want, you can also scroll left, all the way to column 1, to see that you’d probably be able to get a 1RM of 130 pounds.

Whichever method you choose, make sure that you stick with the same method for the entirety of your gym plan!

Baseline testing protocol

Instead of blitzing your entire body in one hard day of testing, it may be more sensible to test up to 9 movement patterns across the course of a week. For context, the following is a template which I like to use a fair bit, as it allows muscles to recover between testing. I focus on picking one benchmark exercise per movement pattern. For example, I always use a barbell back squat for myself, but if you struggle with barbell work, it may be better to try a goblet squat or hack squat machine, for example.

If you can get a 10RM for one exercise in the following 9 categories, you’ll be in a good place for total body strength and fitness.

Day 1

A squat: Barbell back, barbell front, goblet, overhead, hack squat machine, leg press machine.

A horizontal press: Barbell bench press, dumbbell bench press, machine press.

A vertical pull: A bit different - can be bodyweight pullups, machine or band-assisted, or weighted pullups.

Day 2

A hinge: Barbell deadlift, barbell RDL, dumbbell RDL

A vertical press: Barbell overhead press, dumbbell overhead press, standing or seated.

A horizontal pull: Seal row, bench incline row, Pendlay row, bent-over row.

Day 3

Split leg/split stance work: Lunges (forward or reverse, barbell or dumbbell), split squats.

Rotation: Cable rotations, high-to-low chops, landmine rotations

Anti-rotation work: Pallof press (standing or kneeling), maybe single-arm row.

Step Five - Create a training and progression plan

OK, you’ve done the hard work. By this stage, you have a goal in mind, you’ve identified your barriers, picked a weekly schedule, and you know what your current state of fitness is. The hard part is now getting a training plan in place.

Without giving away too many secrets, you could do a lot worse than to follow a similar training plan to your testing week. This would mean a focus on those 9 movement patterns split across 2/3 sessions per week, depending on your own preference. You can also add in some accessory exercises, like single-arm or single-leg exercises, core or trunk training, calf training, plyometrics, etc. I’ve written plenty of newsletters on these previously. For example, a Monday could look like:

Treadmill walking as a warm-up

Compound lifts: Barbell squats, dumbbell bench press, band-assisted pull-ups

Accessory work: Single-arm rows, calf raises, and box jumps.

Finisher: 5x60s efforts on the ski-erg.

Once you have a training plan in place, the important thing is to apply the principles of progressive overload. This means that each week, you should be aiming for a ~5% increase in training volume (load x reps). Trainers are more than capable of doing this for you, but you can track this yourself if you don’t mind numbers. I pick those key exercises which I performed in testing, and use either some software or a simple MS Excel document to track volume. In the example below, you’ll see how I can manipulate sets, reps and load to increase training volume sensibly and sustainably. Sometimes, the training weight or load needs to be reduced to allow for a greater training volume.

Whilst tracking isn’t essential, especially in the opening weeks of your training plan, it will help you defeat plateaus when the time comes.

Step 6 - Re-test and/or achieve your goal

Once you’re in a routine, the next step is just staying consistent and hitting your goal. If you’re choosing a goal which directly relates to gym performance, then you’ll have to wait until your re-testing period, which should be at the time which you outlined in your goal-setting step (remember, good goals have a time-frame). If your goal is determined by gym consistency, then break your plan into 4-6 week blocks, and check in on your progress regularly.

If you slip up and break the habit, the key is to find out why. Maybe you hit a barrier you weren’t expecting, or something completely out of your hands came up. This is OK! Re-assess, modify the goal or plan as needed, then get back into it as soon as you feel ready to. If you need any help with this step, send me a message by hitting the button below, and I’ll give you some tips.

Good luck - give it a go and see what you can achieve!

Thank you for the post, useful for eternal procrastinators like me.