A word that many of you may have heard of, but one which is often associated with old age and frailty. Whilst this is true, you may be surprised by how early this process begins...

What is it?

The word actually has roots in the Greek and Latin languages: ‘Sarx’ or ‘sarc’ meaning flesh, and ‘penia’ indicating a loss of said flesh. So, literally, this means a loss of flesh, which might sound dramatic, but actually isn’t wrong. Technically, sarcopenia is an age-related loss of lean tissue, such as skeletal muscle, which also recognises the subsequent loss of muscular strength and function. It is important to note the difference between sarcopenia and muscle wastage due to disease – this is a different phenomenon entirely.

Here’s the catch: Whenever we hear the words ‘age-related’, we may instantly envisage a frail individual, retired, sat in an arm chair, with a walking stick to help them to move around the house. However, this process begins decades beforehand. In fact, in sedentary individuals, this can begin as early as the age of 30, but does typically start a few years later, from 35 onwards.

Don’t believe it? MRI scans do help to visualise these changes. In the image below, the effects of sarcopenia are easily seen. Images D and E both show the thigh (imagine cut in half widthways, and then looking down from above) of two 66-year-olds. One of these individuals (E) is regularly active, as indicated by the greater presence and quality of muscle mass, the dark grey matter. The less active individual (D) has greater fat levels surrounding the muscle (light grey), but also has much less muscle mass. This shows a stark difference to a 24-year-old (C) who clearly has ample muscle mass and very little fat tissue.

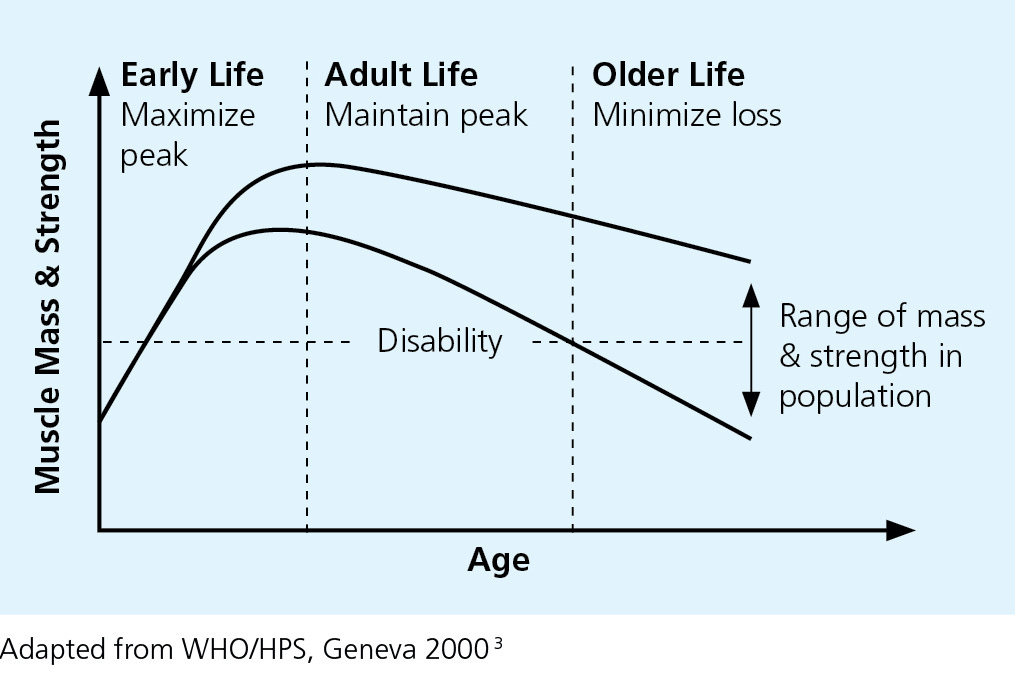

These results make sense when you consider the graph below. In it, you can see that in general, muscle mass and strength tend to increase up the age of around 25. Even before this peak, there is some variation in muscle mass and strength between individuals. Some of this will be genetic, but some of the variation will be due to lifestyle factors such as exercise habits and physical activity levels.

It can be assumed that the first vertical dashed line here represents the age of 35-ish. After this point, muscle mass declines steadily, at a rate of 3-8% per decade until the age of about 60, where this decrease is accelerated and represented by the ‘older life’ segment of the graph.

You’ll notice that this image also includes a threshold called ‘disability’. This is because there comes a point at which an individual does not possess the necessary strength or functionality to live independently. These people may be unable to sit/get up from the toilet or sofa by themselves, or be able to lift their leg into the bath. Daily tasks such as self-care and maintenance, cooking, cleaning, or tidying may simply be too exhausting for them. These individuals represent up to 13% of over-60s and 50% of over-80s; it is much more common than you may think.

Why is it important to avoid sarcopenia?

Unfortunately, sarcopenia has the ability to magnify other age-related health disorders. For example, we also know that bone mass can decrease as we get older, leading to osteopenia (osteo=bone, penia=loss of) and osteoporosis. Therefore, the lack of muscular strength associated with sarcopenia may lead to more frequent falls, which are more likely to result in fractures in those with osteopenia or osteoporosis. In turn, this is likely to lead to further deconditioning. It is easy to see how some older individuals get stuck in a downwards spiral towards frailty.

What can we do to avoid sarcopenia?

There are some very simple but effective measures to combat the onset of sarcopenia. Specific exercise and nutritional interventions may be effective at preventing the loss of lean tissue as we age.

Exercise

Hitting the recommended targets for both cardiorespiratory and resistance exercise will go a long way to preventing sarcopenia. Performing 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (fast walking, gardening), or 75-minutes of vigorous intensity activity (running, cycling, swimming) each week will improve metabolic health, which so often deteriorates as we lose muscle mass.

In addition to this, ensuring that one performs resistance training of the major muscle groups on at least 2 days each week will help to preserve lean tissue. This can be in the form of resistance bands, free weights, machine weights or bodyweight exercises, but a focus on compound movements such as squats will improve the efficiency of these exercise sessions.

Daily practice of balance and co-ordination exercise will also help. As we know, frailty and loss of muscle mass are associated with a greater risk of falls, which can be particularly problematic as we age. By strengthening the muscles through resistance training, the body is better equipped to: a) not fall in the first place, b) possess the strength to maintain upright if we trip, and c) get up from the floor if we do fall all the way. Training balance, for example, by standing on one leg whilst brushing our teeth, prepares the body for being thrown off balance and further helps in case of a trip.

Nutrition

We also know that many of us do not ingest adequate protein to aid in the maintenance of muscle mass. In the UK, our (still low) recommended targets for protein intake are set at 0.75-0.80g of protein, per kilogramme of body weight per day. For a 100kg individual, this would equate to a daily intake of 75-80g of protein. However, recent research has shown that, especially in older adults, fewer than half of us actually hit these goals. A combined approach of adequate protein intake and resistance training will help to offset the deterioration of lean tissue from the age of ~35.

Conclusion

Yes, sarcopenia may not sound like an issue until we get to retirement age, but it is important to address the decline in lean tissue that begins much earlier than that. Building healthy exercise and nutrition habits early on in life significantly decreases the risk of sarcopenia and frailty later in life. It may be an exercise in delayed gratification, but it certainly pays off, not only in the case of sarcopenia, but also for heart, metabolic, and brain health, too.

1 gram per pound of weight is what I try to achieve.

Given an old, say 80+ person with advanced sarcopenia, what, if anything, might be done to arrest the further progession of sarcopenia and disability?