Coaches should be familiar with this term already, but do you, as a client or athlete, understand what it is or what it entails, or the scientific reasoning behind it?

Today’s blog is written in association with Fitlife Summertown. If you live in the Oxford area and looking for PT, or maybe you don’t live nearby but are looking for remote specialist exercise support, get in touch by tapping ‘Message Ben Howard’ at the bottom of the page!

How many of you, as clients or athletes, have been progressing happily with your current gym plan, only for your trainer (the fiend!) to hit you with the dreaded phrase: “We are moving onto a different block of training now…”? If the answer is yes, then you have been subjected to training periodisation.

From your point of view, this may feel frustrating at first. You might just be mastering 3 sets of 8 repetitions at a certain weight during your split squats, only to be told that you’re about to move to a heavier weight, for 4 repetitions for the next few weeks. However, it is a good thing! This is proof that your trainer has not only planned their sessions well in advance, and worked backwards from an end-goal, but it also means that you’re much less likely to succumb to overtraining or injury in the long run.

So, what is periodisation?

“Periodisation is the logical and systematic process of sequencing and integrating training interventions in order to achieve peak performance at appropriate time points.”1

In layman’s terms, it refers to the altering of certain variables (training weight, intensity, rest, tempo, or frequency) to allow for optimal performance towards your desired goal.

General Adaptation Syndrome

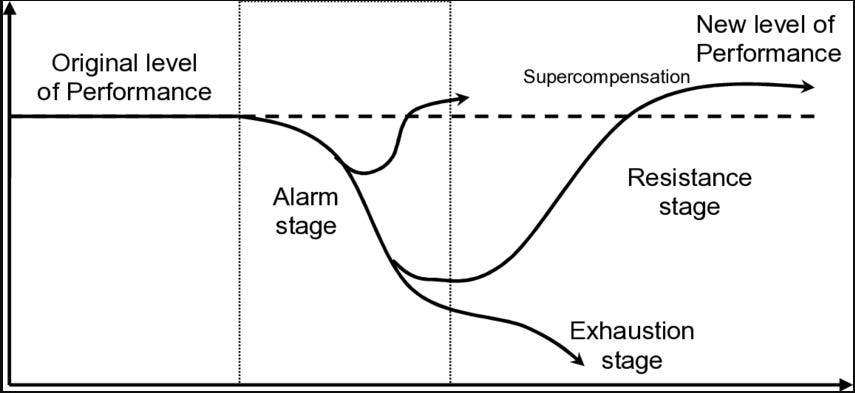

To understand why periodisation is important, we must first come to terms with the concept of General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS; yes, I realise this acronym is going to leave me vulnerable here…). You will have experienced the effects of GAS (very funny) in your own training. Have you ever finished a gym session featuring a new exercise or heavier weight, then ached for days, but repeated it again next week and not ached so much? Or maybe the new weight felt easier? This is how GAS works. I have copied in a figure below to help visualise the process.

Stage 1 - Alarm

A new stressor, such as a different exercise, heavier weight, or increased workload, fatigues the muscle and causes an immediate decrease in performance (i.e. - cannot lift that weight for a final set of X repetitions).

Stage 2 - Resistance

The body adapts to this new stimulus. After the final set of the workout, a series of recovery adaptations take place, specific to the induced demand of the workout.

Stage 3A - Supercompensation

This appropriate level of stress and recovery leads to an improvement in performance, higher than previous baseline levels. This may mean that the workout is less difficult next time.

OR

Stage 3B - Overtraining

The stressors are too strong and inadequate recovery is given. This leads to a steady decline in performance which may lead to overtraining and exhaustion.

The GAS model works very effectively at demonstrating the need for structured, long-term planning with exercise programmes. This is especially true considering that a lack of new training stimulus will also lead to a state of detraining, which is why a varied exercise plan is so important.

Types of periodisation

There are 3 well-reported methods of periodisation:

Block periodisation

As the name suggests, this is the method of dividing a gym programme into blocks of time, called mesocycles, each with a specific focus. For example, there may be an 8-week period with a focus on general preparation (such as 3-6 sets of 8-20 repetitions), followed by a shift to a more strength-based approach (more like 3-5 sets of 3-5 repetitions at a much higher intensity).

Linear periodisation

This approach is recognisable as more of a continual shift in training focus, rather than splitting a programme into discrete blocks. Typically, linear periodisation involves a steady change from high volume, low intensity training (such as 4 sets of 12 repetitions) to low volume, high intensity training (such as 3 sets of 5 repetitions). Instead of these changes taking place every few weeks, each week may see a small shift in stimulus toward the end goal.

Daily undulating periodisation

Just to make things complicated, there is a method of periodisation which involves changing the stimulus on a session-by-session basis. This may present itself as a ‘strength’ focussed session on a Monday, a ‘hypertrophy’ focussed session on a Wednesday, and a power focussed session on a Friday, each with vastly different set and repetition targets. In this case, the total weekly volume and intensity would be measured and recorded by the trainer.

Each method has different pros and cons. The research is fairly undecided on whether there is one superior method, but it is clear that, provided the training stimuli follow the overarching rules of GAS, all methods can be successful in improving performance, reaching goals, and avoiding overtraining.

Final thoughts

So now you understand a little bit more on the scientific justification for altering the training stimulus, and how this can accelerate you toward your goals. If you’re in the middle of your own gym plan and would like a helping hand to introduce your own periodisation, just click or tap the button below and send me a message.

See you next week!

Haff & Triplett (eds), Essentials of Strength and Conditioning 4th Edition, pg 584.