Many of us are, or will be, lucky enough to reach the age of 65. Whilst we can’t stop time, we can choose how well prepared we are to get older. As a reader, you may be over the age of 65 already; if not, you may have relatives of this age. There’s no reason not to exercise because of age; it improves so many aspects of life, including quality of life and ease of activities of daily living.

This newsletter will give you a rough idea of how to exercise older adults AT HOME, including a sample workout session. It won’t require much specialist equipment, and will focus on fundamental movement patterns. Let’s dispel the myth that older adults are too frail to exercise - you’re not going to keel over and kick the can because you started your day with some push-ups!

Housekeeping

Here are a few quick reminders before we begin:

You can access the entire Muscle Monday education series for FREE here.

You can download my FREE guide, 20 Habits to Change Your Life, here.

You can get 10% off EVERY order, present and future, at Awesome Supplements by using the code ‘EZEP’ at checkout. Special shout out to the Hybrid Athlete bundle, now available.

Why is exercise so important as we age?

There are three processes which occur as we age to consider:

Decline of muscle mass (sarcopenia)

Decline of cardiorespiratory function

Decline of bone mass (osteopenia, and then osteoporosis)

Let’s go through these one by one.

Sarcopenia

I’ve previously written about sarcopenia, so will put a link to it just below.

Put simply, from the age of 30-ish, the phrase ‘use it or lose it’ takes on even greater significance. In our 20s, we take our lean tissue for granted. We are able to perform daily tasks, exercise pretty much however we like, and get away with exercise imperfections without too many serious consequences. Sadly, this changes as we enter our 30s. From thereon, we lose on average 8% of our muscle mass per decade, and in some individuals, this can exceed 10%.

This may not sound too bad, but it compounds over time. Suddenly, it becomes harder to stand up and get out of that chair, or you can’t walk the dog as easily as you once did. By the time you reach 80 years old, you may have only 60% of the lean tissue compared to when you were 30.

Decline of cardiorespiratory function

Even if we ignore this sarcopenia, we still have the issue of cardiorespiratory decline. The metric here is VO2max and refers to the ability of the body to take in, transport, and utilise oxygen. The higher the VO2max, the better your cardiorespiratory fitness. Again, provided you don’t exercise regularly, this number declines with age. In a similar manner to muscle mass, VO2max also declines at a rate of ~10% per decade. However, this process starts from as early as 25 years old, up to ten years sooner than sarcopenia.

This is important as there is a critical level of VO2max which is associated with loss of independence. If you’ve ever noticed somebody who gets out of breath simply tidying up, climbing stairs, getting up from a chair, or washing the dishes, then chances are this person is flirting with that threshold.

As you can see in the image below, a sedentary individual is much more likely to cross the threshold earlier in life, compared to a trained individual.

Osteopenia and osteoporosis

Osteopenia is characterised by a bone mineral density which lies between -1 to -2.5 standard deviations of the young adult mean average. A bone mineral density even lower than -2.5 standard deviations is defined as osteoporosis. It is a more rapid decline in post-menopausal women, although both men and women see a decline in bone density after the ages of 30-40. There are several factors, including genetic, mechanical, and hormonal influences.

Lower bone mineral density can lead to a greater risk of fractures, which is the main reason that we can be overprotective of our older populations, especially when it comes to exercise. However, since exercise, particularly weight-bearing exercise such as walking and resistance training, is a stimulus for bone mineral growth, there is a decent body of evidence to show that osteopenia and osteoporosis can be delayed or even stopped through sufficient physical activity.

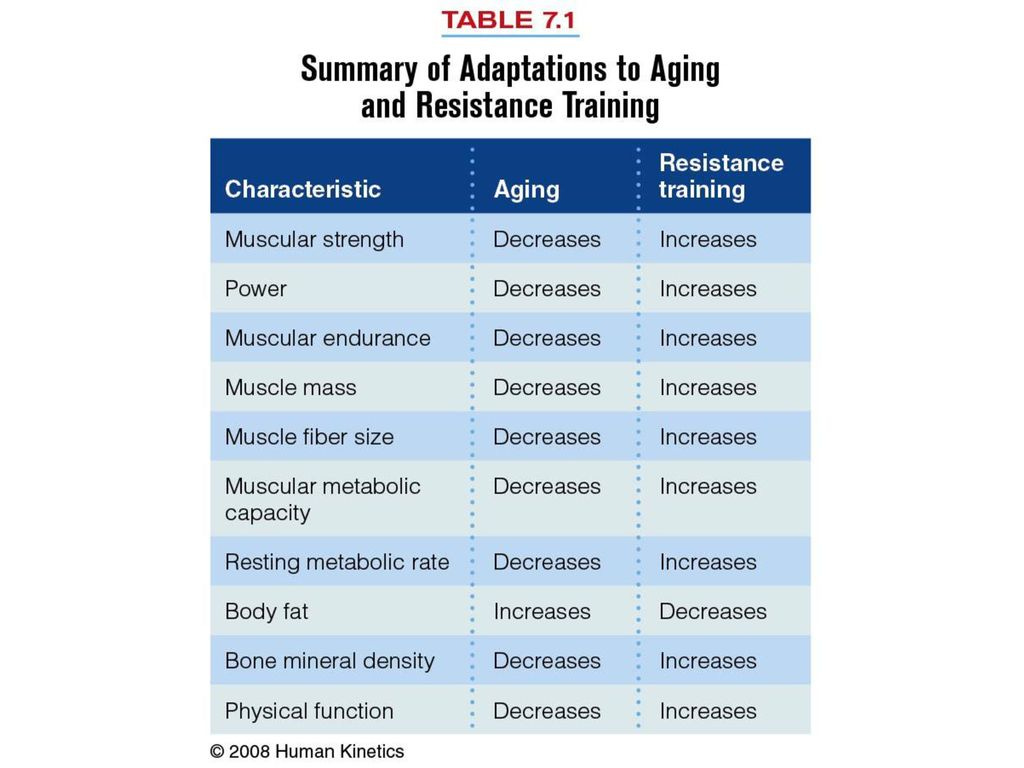

While the above three processes are important to note, they are not the only changes which occur as we age. I have inserted a table below which outlines some age-related performance changes and how resistance training (strength training) can offset these changes.

How should training differ compared to younger populations?

For most of us, the main difference will be that recovery takes that little bit longer as we get older. However, there are other considerations before beginning a training plan, including:

Current health status (in some cases, a medical professional should be consulted before commencing a new plan);

Previous exercise experience;

Current nutritional status

Your friendly neighbourhood specialist (hi) will be able to create a sensible a personalised plan based on these factors.

There are some further considerations and adaptations, as per the guidelines set out by the NSCA:1

A thorough warm-up consisting of 5-10 minutes of a pulse raiser, some static stretching, and/or calisthenics (bodyweight exercises);

A stimulus which does not overtax the musculoskeletal system;

If necessary, an avoidance of the Valsalva manoeuvre;

A pain-free range of motion;

Between 48-72 hours recovery between resistance exercise sessions;

A qualified and accredited professional to oversee the exercises (that’s me!).

A sample workout based on the above guidelines

So, how can we put this all together to make a sample exercise session that would be sensible for an older adult who is free of serious health complications and/or has had medical clearance to begin a supervised exercise plan?

The Warm-up

The warm-up should be in 3 stages as per the guidelines above.

A heart-rate raiser (5-10 mins, can be broken into 5x1 minute efforts):

Some form of calisthenic (bodyweight exercise) circuit

Complete each of the above for 2 rounds of 12-20 repetitions each, taking as much rest as necessary between exercises.

Some simple stretches

Complete each of the above for 30-45 seconds each, taking as much time between stretches as needed. Complete each stretch 2-3 times, either as a circuit or by performing the same stretch consecutively.

The main session

It is important to note that, for some individuals, the warm-up alone may be difficult enough. If this is the case, that is fine! Remember, the important thing here is to find a stimulus which is correct for the INDIVIDUAL. When it comes to exercise, something is better than nothing, and (apart from extreme cases), more is better than less. If the warm-up is enough, good on you!

For those who feel as though they can do a bit more, then the following may just work. Below, I shall create 5 stations. Each station will have a choice of three exercises (beginner, intermediate, advanced). Pick ONE of these options from each station. Some may require basic equipment, such as a can of beans, a water bottle, or a dumbbell if possible.

Once you have picked your five exercises, you may perform each exercise for 90 seconds. This is to be done at your own pace, so don’t go off too fast. If needed, you can pause at any time during the 90 seconds. For one-sided exercises, such as side planks, complete both sides before moving on to the next exercise.

After the 90 seconds are complete, rest for up to 90 seconds before starting the next exercise in the sequence, and keep this 90s on, 90s off routine going until you have performed each of the 5 exercises.

You can then repeat this circuit up to 5 times in total.

To summarise then:

90 seconds of exercise, followed by 90 seconds of rest;

Move on to the next exercise

Repeat up to 5x.

Station 1: Lower body

Station 2: Upper body

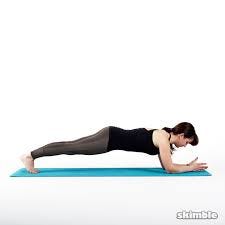

Station 3: Static

Station 4: Lower body

Station 5: Balance and co-ordination

The cool-down

Normally, I’m not a fan of a cool down, but the NSCA recommends stretching before and after a workout if possible. With that in mind, I’d recommend either performing the same stretches as the warm-up again, or the following. Again, perform each stretch for 30-45 seconds, 2-3 times.

The bottom line

This workout won’t be perfect for everyone. As we age, our bodies become more unique, and this requires even more specific exercise intervention. However, this sample workout hopefully provides some idea of how to structure and perform an exercise session for those over the age of 65, to reduce injury risk and optimise adaptations to combat the aging process.

If you have any questions about this workout, please do get in touch with my by hitting the button below. We are also less than 100 subscribers away from hitting the magic 1000, so please do share and subscribe if you haven’t already! Thanks again and see you next Wednesday!

Haff & Triplett (eds), Essentials of Strength and Conditioning, Human Kinetics.